When our repentance is set in stone

- Ross Moughtin

- Aug 15, 2025

- 3 min read

I had to do a double take. This wasn’t your usual memorial plaque—it was an apology. A very public apology.

On Wednesday, during our visit to Tours in the Loire Valley, we wandered through the beautiful Basilica of Saint Martin. The current building is barely a century old; its predecessors were destroyed in turn by the Vikings, the Huguenots, and finally the French Revolutionaries. This place has had a tough history!

Today, the basilica is an important stop for pilgrims travelling the Via Sancti Martini, some coming from as far away as Sicily or Poland. With journeys stretching up to 1,000 kilometres, it’s easy to imagine the temptation to celebrate such devotion with grandeur and ceremony.

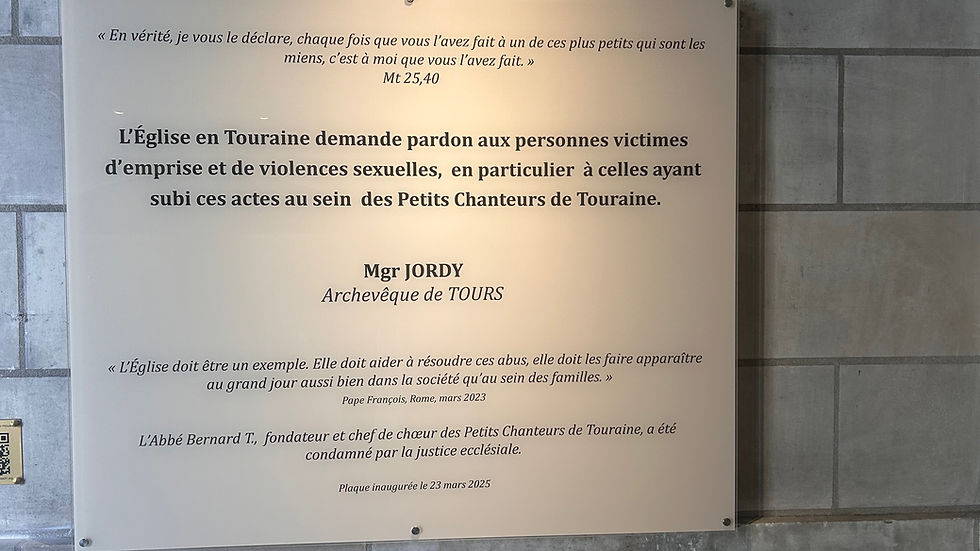

And yet there it was—at the entrance—a simple, clearly new plaque:

L’Église en Touraine demande pardon aux personnes victimes d’emprise et de violences sexuelles, en particulier à celles ayant subi ces actes au sein des Petits Chanteurs de Touraine.

Google Translate renders this as:

The Church in Touraine asks forgiveness from people who are victims of control and sexual violence, in particular from those who suffered these acts within the Petits Chanteurs de Touraine.

It was signed by Mgr Jordy, the Archbishop of Tours.

Clearly, there was a story here. Intrigued, I set out to discover the history behind this plaque.

Bernard Tartu founded the choir school for Tours Cathedral, Les Petits Chanteurs de Touraine, in 1954. He was ordained a priest in 1961, served as choir director in several cathedrals, and returned to Tours in 1997.

It’s a depressingly typical story. As head of the choir, Tartu had daily, direct access to boys aged roughly 7–15 during rehearsals and tours—an environment ripe for abuse with little oversight.

The first complaint was filed in 2006, when a former chorister alleged that Tartu sexually abused him between 1968 and 1975 under the pretext of “medical examinations,” causing life-long trauma.

It gets worse.

Because the alleged abuse occurred decades earlier, French law initially blocked civil or criminal prosecution. Nevertheless, reports later emerged that up to 20 victims may have come forward, with around nine filing canonical appeals.

In December 2021, Archbishop Jordy suspended Tartu from official duties and removed him from diocesan hospitality, citing the credibility of the allegations.

This terrible situation was only resolved last November, following the French Roman Catholic Church’s establishment of the Tribunal Pénal Canonique National in 2022. The tribunal found Tartu, then 88, guilty of sexual abuse of minors, banning him from public liturgical roles and spiritual direction involving minors, and placing him effectively under house arrest.

That was all the Church could do, and to its credit, the victims expressed relief at the formal recognition of their suffering during a press conference.

The memorial plaque, honouring victims of sexual violence in the Church—including Tartu’s survivors—was unveiled at the Basilica this March. It quotes Pope Francis, translated here by Google:

“The Church must be an example. It must help resolve these abuses, it must bring them to light, both within society and within families.”

The whole situation is a mess. That Tartu was able to exploit generations of choir boys without intervention is appalling. The plaque itself is headed by a verse from Jesus:

“Truly I tell you, whatever you did for one of the least of these brothers and sisters of mine, you did for me.” (Matthew 25:40)

For all of us, whatever mess we may have caused in life, the first step is simply to acknowledge our responsibility. We must refuse self-serving excuses and deny any attempt at denial. The way forward is to say with the prodigal son:

“Father, I have sinned against heaven and against you.”

Amazingly, through the power of Jesus’ cross, we are accepted and forgiven. We are invited into the banquet—a profound act of grace.

But repentance isn’t just an event between us and God. In reality, we have hurt, even damaged, other people—and we need to seek their forgiveness. They may choose to withhold it; that is their prerogative. Our attempt at reconciliation must be genuine, and here, as always, we need the guidance of the Holy Spirit.

Sometimes, as in the case of the Diocese of Tours, a public acknowledgment is necessary—even set in stone, so to speak. It greets the tired pilgrim at the basilica entrance. As Frank Buchman, founder of the Oxford Group, put it:

“If the sin was a public one, restitution might involve making a public confession.”

We pray that such public acknowledgements become not rare exceptions but natural expressions of a Church unafraid to face its past, and determined to let grace, not shame, have the final word.

Comments